This advisory uses the MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK®) version 7 framework. See the ATT&CK for Enterprise version 7 for all referenced threat actor tactics and techniques.

This joint cybersecurity advisory was coauthored by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). CISA and the FBI are aware of an Iranian advanced persistent threat (APT) actor targeting U.S. state websites—to include election websites. CISA and the FBI assess this actor is responsible for the mass dissemination of voter intimidation emails to U.S. citizens and the dissemination of U.S. election-related disinformation in mid-October 2020. (Reference FBI FLASH message ME-000138-TT, disseminated October 29, 2020). Further evaluation by CISA and the FBI has identified the targeting of U.S. state election websites was an intentional effort to influence and interfere with the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

Click here for a PDF version of this report.

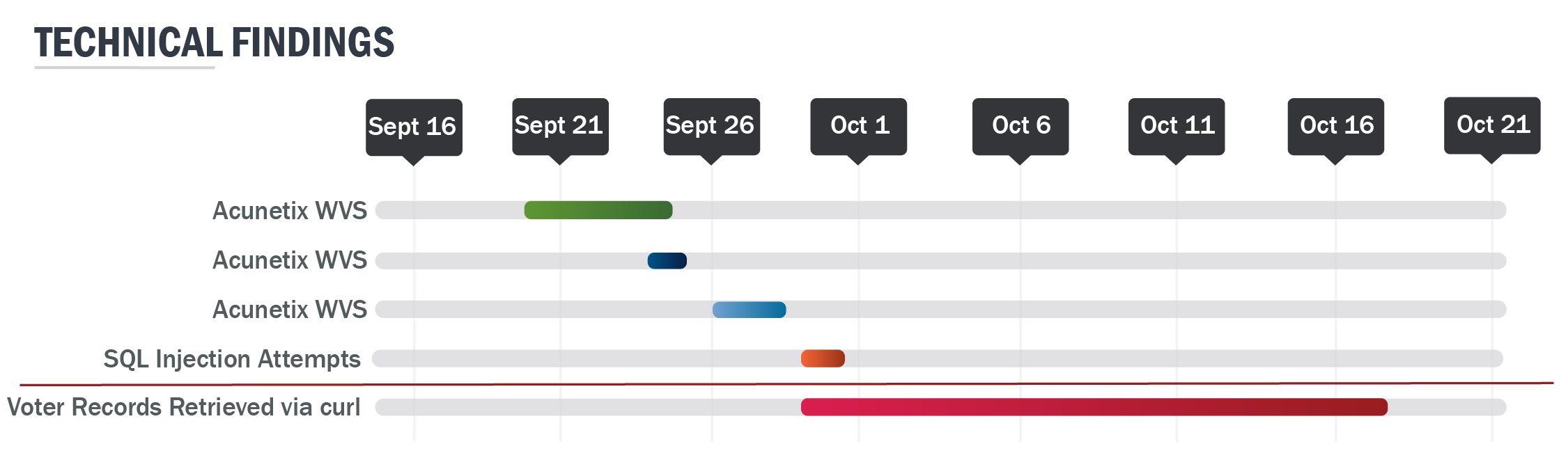

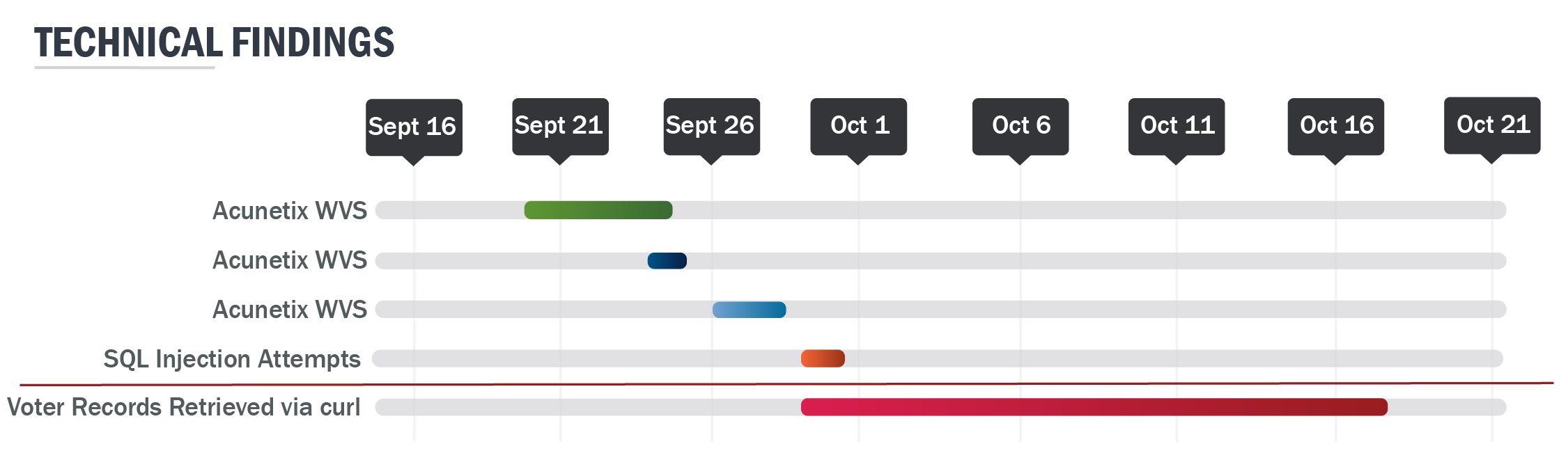

Analysis by CISA and the FBI indicates this actor scanned state websites, to include state election websites, between September 20 and September 28, 2020, with the Acunetix vulnerability scanner (Active Scanning: Vulnerability Scanning [T1595.002]). Acunetix is a widely used and legitimate web scanner, which has been used by threat actors for nefarious purposes. Organizations that do not regularly use Acunetix should monitor their logs for any activity from the program that originates from IP addresses provided in this advisory and consider it malicious reconnaissance behavior.

Additionally, CISA and the FBI observed this actor attempting to exploit websites to obtain copies of voter registration data between September 29 and October 17, 2020 (Exploit Public-Facing Application [T1190]). This includes attempted exploitation of known vulnerabilities, directory traversal, Structured Query Language (SQL) injection, web shell uploads, and leveraging unique flaws in websites.

CISA and the FBI can confirm that the actor successfully obtained voter registration data in at least one state. The access of voter registration data appeared to involve the abuse of website misconfigurations and a scripted process using the cURL tool to iterate through voter records. A review of the records that were copied and obtained reveals the information was used in the propaganda video.

CISA and FBI analysis of identified activity against state websites, including state election websites, referenced in this product cannot all be fully attributed to this Iranian APT actor. FBI analysis of the Iranian APT actor’s activity has identified targeting of U.S. elections’ infrastructure (Compromise Infrastructure [T1584]) within a similar timeframe, use of IP addresses and IP ranges – including numerous virtual private network (VPN) service exit nodes – which correlate to this Iran APT actor (Gather Victim Host Information [T1592)]), and other investigative information.

Reconnaissance

The FBI has information indicating this Iran-based actor attempted to access PDF documents from state voter sites using advanced open-source queries (Search Open Websites and Domains [T1539]). The actor demonstrated interest in PDFs hosted on URLs with the words “vote” or “voter” and “registration.” The FBI identified queries of URLs for election-related sites.

The FBI also has information indicating the actor researched the following information in a suspected attempt to further their efforts to survey and exploit state election websites.

- YOURLS exploit

- Bypassing ModSecurity Web Application Firewall

- Detecting Web Application Firewalls

- SQLmap tool

Acunetix Scanning

CISA’s analysis identified the scanning of multiple entities by the Acunetix Web Vulnerability scanning platform between September 20 and September 28, 2020 (Active Scanning: Vulnerability Scanning [T1595.002]).

The actor used the scanner to attempt SQL injection into various fields in /registration/registration/details with status codes 404 or 500:

/registration/registration/details?addresscity=-1 or 3*2<(0+5+513-513) -- &addressstreet1=xxxxx&btnbeginregistration=begin voter registration&btnnextelectionworkerinfo=next&btnnextpersonalinfo=next&btnnextresdetails=next&btnnextvoterinformation=next&btnsubmit=submit&chkageverno=on&chkageveryes=on&chkcitizenno=on&chkcitizenyes=on&chkdisabledvoter=on&chkelectionworker=on&chkresprivate=1&chkstatecancel=on&dlnumber=1&dob=xxxx/x/x&[email protected]&firstname=xxxxx&gender=radio&hdnaddresscity=&hdngender=&last4ssn=xxxxx&lastname=xxxxxinjjeuee&[email protected]&[email protected]&[email protected]&[email protected]&mailaddressstate=aa&[email protected]&[email protected]&middlename=xxxxx&overseas=1&partycode=a&phoneno1=xxx-xxx-xxxx&phoneno2=xxx-xxx-xxxx&radio=consent&statecancelcity=xxxxxxx&statecancelcountry=usa&statecancelstate=XXaa&statecancelzip=xxxxx&statecancelzipext=xxxxx&suffixname=esq&[email protected]

Requests

The actor used the following requests associated with this scanning activity.

2020-09-26 13:12:56 x.x.x.x GET /x/x v[$acunetix]=1 443 - x.x.x.x Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+6.1;+WOW64)+AppleWebKit/537.21+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/41.0.2228.0+Safari/537.21 - 200 0 0 0

2020-09-26 13:13:19 X.X.x.x GET /x/x voterid[$acunetix]=1 443 - x.x.x.x Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+6.1;+WOW64)+AppleWebKit/537.21+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/41.0.2228.0+Safari/537.21 - 200 0 0 1375

2020-09-26 13:13:18 .X.x.x GET /x/x voterid=;print(md5(acunetix_wvs_security_test)); 443 - X.X.x.x

User Agents Observed

CISA and FBI have observed the following user agents associated with this scanning activity.

Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+6.1;+WOW64)+AppleWebKit/537.21+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/41.0.2228.0+Safari/537.21 - 500 0 0 0

Mozilla/5.0+(X11;+U;+Linux+x86_64;+en-US;+rv:1.9b4)+Gecko/2008031318+Firefox/3.0b4

Mozilla/5.0+(X11;+U;+Linux+i686;+en-US;+rv:1.8.1.17)+Gecko/20080922+Ubuntu/7.10+(gutsy)+Firefox/2.0.0.17

Exfiltration

Obtaining Voter Registration Data

Following the review of web server access logs, CISA analysts, in coordination with the FBI, found instances of the cURL and FDM User Agents sending GET requests to a web resource associated with voter registration data. The activity occurred between September 29 and October 17, 2020. Suspected scripted activity submitted several hundred thousand queries iterating through voter identification values, and retrieving results with varying levels of success [Gather Victim Identity Information (T1589)]. A sample of the records identified by the FBI reveals they match information in the aforementioned propaganda video.

Requests

The actor used the following requests.

2020-10-17 13:07:51 x.x.x.x GET /x/x voterid=XXXX1 443 - x.x.x.x curl/7.55.1 - 200 0 0 1406

2020-10-17 13:07:55 x.x.x.x GET /x/x voterid=XXXX2 443 - x.x.x.x curl/7.55.1 - 200 0 0 1390

2020-10-17 13:07:58 x.x.x.x GET /x/x voterid=XXXX3 443 - x.x.x.x curl/7.55.1 - 200 0 0 1625

2020-10-17 13:08:00 x.x.x.x GET /x/x voterid=XXXX4 443 - x.x.x.x curl/7.55.1 - 200 0 0 1390

Note: incrementing voterid values in cs_uri_query field

User Agents

CISA and FBI have observed the following user agents.

FDM+3.x

curl/7.55.1

Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+6.1;+WOW64)+AppleWebKit/537.21+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/41.0.2228.0+Safari/537.21 - 500 0 0 0

Mozilla/5.0+(X11;+U;+Linux+x86_64;+en-US;+rv:1.9b4)+Gecko/2008031318+Firefox/3.0b4

See figure 1 below for a timeline of the actor’s malicious activity.

Figure 1: Overview of malicious activity

Detection

Acunetix Scanning

Organizations can identify Acunetix scanning activity by using the following keywords while performing log analysis.

$acunetixacunetix_wvs_security_test

Indicators of Compromise

For a downloadable copy of IOCs, see AA20-304A.stix.

Disclaimer: Many of the IP addresses included below likely correspond to publicly available VPN services, which can be used by individuals all over the world. Although this creates the potential for false positives, any activity listed should warrant further investigation. The actor likely uses various IP addresses and VPN services.

The following IPs have been associated with this activity.

- 102.129.239[.]185 (Acunetix Scanning)

- 143.244.38[.]60 (Acunetix Scanning and cURL requests)

- 45.139.49[.]228 (Acunetix Scanning)

- 156.146.54[.]90 (Acunetix Scanning)

- 109.202.111[.]236 (cURL requests)

- 185.77.248[.]17 (cURL requests)

- 217.138.211[.]249 (cURL requests)

- 217.146.82[.]207 (cURL requests)

- 37.235.103[.]85 (cURL requests)

- 37.235.98[.]64 (cURL requests)

- 70.32.5[.]96 (cURL requests)

- 70.32.6[.]20 (cURL requests)

- 70.32.6[.]8 (cURL requests)

- 70.32.6[.]97 (cURL requests)

- 70.32.6[.]98 (cURL requests)

- 77.243.191[.]21 (cURL requests and FDM+3.x (Free Download Manager v3) enumeration/iteration)

- 92.223.89[.]73 (cURL requests)

CISA and the FBI are aware the following IOCs have been used by this Iran-based actor. These IP addresses facilitated the mass dissemination of voter intimidation email messages on October 20, 2020.

- 195.181.170[.]244 (Observed September 30 and October 20, 2020)

- 102.129.239[.]185 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 104.206.13[.]27 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 154.16.93[.]125 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 185.191.207[.]169 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 185.191.207[.]52 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 194.127.172[.]98 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 194.35.233[.]83 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 198.147.23[.]147 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 198.16.66[.]139(Observed September 30, 2020)

- 212.102.45[.]3 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 212.102.45[.]58 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 31.168.98[.]73 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 37.120.204[.]156 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 5.160.253[.]50 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 5.253.204[.]74 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 64.44.81[.]68 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 84.17.45[.]218 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 89.187.182[.]106 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 89.187.182[.]111 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 89.34.98[.]114 (Observed September 30, 2020)

- 89.44.201[.]211 (Observed September 30, 2020)

Recommendations

The following list provides recommended self-protection mitigation strategies against cyber techniques used by advanced persistent threat actors:

- Validate input as a method of sanitizing untrusted input submitted by web application users. Validating input can significantly reduce the probability of successful exploitation by providing protection against security flaws in web applications. The types of attacks possibly prevented include SQL injection, Cross Site Scripting (XSS), and command injection.

- Audit your network for systems using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) and other internet-facing services. Disable unnecessary services and install available patches for the services in use. Users may need to work with their technology vendors to confirm that patches will not affect system processes.

- Verify all cloud-based virtual machine instances with a public IP, and avoid using open RDP ports, unless there is a valid need. Place any system with an open RDP port behind a firewall and require users to use a VPN to access it through the firewall.

- Enable strong password requirements and account lockout policies to defend against brute-force attacks.

- Apply multi-factor authentication, when possible.

- Maintain a good information back-up strategy by routinely backing up all critical data and system configuration information on a separate device. Store the backups offline, verify their integrity, and verify the restoration process.

- Enable logging and ensure logging mechanisms capture RDP logins. Keep logs for a minimum of 90 days and review them regularly to detect intrusion attempts.

- When creating cloud-based virtual machines, adhere to the cloud provider’s best practices for remote access.

- Ensure third parties that require RDP access follow internal remote access policies.

- Minimize network exposure for all control system devices. Where possible, critical devices should not have RDP enabled.

- Regulate and limit external to internal RDP connections. When external access to internal resources is required, use secure methods, such as a VPNs. However, recognize the security of VPNs matches the security of the connected devices.

- Use security features provided by social media platforms; use strong passwords, change passwords frequently, and use a different password for each social media account.

- See CISA’s Tip on Best Practices for Securing Election Systems for more information.

General Mitigations

Keep applications and systems updated and patched

Apply all available software updates and patches and automate this process to the greatest extent possible (e.g., by using an update service provided directly from the vendor). Automating updates and patches is critical because of the speed of threat actors to create new exploits following the release of a patch. These “N-day” exploits can be as damaging as zero-day exploits. Ensure the authenticity and integrity of vendor updates by using signed updates delivered over protected links. Without the rapid and thorough application of patches, threat actors can operate inside a defender’s patch cycle. Additionally, use tools (e.g., the OWASP Dependency-Check Project tool ) to identify the publicly known vulnerabilities in third-party libraries depended upon by the application.

Scan web applications for SQL injection and other common web vulnerabilities

Implement a plan to scan public-facing web servers for common web vulnerabilities (e.g., SQL injection, cross-site scripting) by using a commercial web application vulnerability scanner in combination with a source code scanner. Fixing or patching vulnerabilities after they are identified is especially crucial for networks hosting older web applications. As sites get older, more vulnerabilities are discovered and exposed.

Deploy a web application firewall

Deploy a web application firewall (WAF) to prevent invalid input attacks and other attacks destined for the web application. WAFs are intrusion/detection/prevention devices that inspect each web request made to and from the web application to determine if the request is malicious. Some WAFs install on the host system and others are dedicated devices that sit in front of the web application. WAFs also weaken the effectiveness of automated web vulnerability scanning tools.

Deploy techniques to protect against web shells

Patch web application vulnerabilities or fix configuration weaknesses that allow web shell attacks, and follow guidance on detecting and preventing web shell malware. Malicious cyber actors often deploy web shells—software that can enable remote administration—on a victim’s web server. Malicious cyber actors can use web shells to execute arbitrary system commands commonly sent over HTTP or HTTPS. Attackers often create web shells by adding or modifying a file in an existing web application. Web shells provide attackers with persistent access to a compromised network using communications channels disguised to blend in with legitimate traffic. Web shell malware is a long-standing, pervasive threat that continues to evade many security tools.

Use multi-factor authentication for administrator accounts

Prioritize protection for accounts with elevated privileges, remote access, or used on high-value assets. Use physical token-based authentication systems to supplement knowledge-based factors such as passwords and personal identification numbers (PINs). Organizations should migrate away from single-factor authentication, such as password-based systems, which are subject to poor user choices and more susceptible to credential theft, forgery, and password reuse across multiple systems.

Remediate critical web application security risks

First, identify and remediate critical web application security risks. Next, move on to other less critical vulnerabilities. Follow available guidance on securing web applications.

How do I respond to unauthorized access to election-related systems?

Implement your security incident response and business continuity plan

It may take time for your organization’s IT professionals to isolate and remove threats to your systems and restore normal operations. In the meantime, take steps to maintain your organization’s essential functions according to your business continuity plan. Organizations should maintain and regularly test backup plans, disaster recovery plans, and business continuity procedures.

Contact CISA or law enforcement immediately

To report an intrusion and to request incident response resources or technical assistance, contact CISA ([email protected] or 888-282-0870) or the FBI through a local field office or the FBI’s Cyber Division ([email protected] or 855-292-3937).

Resources

Source…